Nima's notes

How humans understand identity

Lack of great user experiences is often raised as one of decentralized identity’s (and public blockchain’s) missing ingredients for ubiquitous adoption. However to arrive at usable experiences across the industry, we first need to reach consensus around basic user personas and mental models, then design and build interoperable system accordingly.

In “the internet’s missing identity layer” we took a stab at an acceptable set of personas and solution criteria for this self described identity system.

In “Economics of identity systems” we also observed how users already interact with identity concepts in their day-to-day economic activities, and the artifacts they use as tools to accomplish them.

This article explores the different aspects of how a typical user understands concepts related to identity through the use of economic, cognitive, and design lenses, as well as through historical observation and application of first principles.

Summary

No typical human explicitly understand abstract terms like “identity”. They may intuitively understand some well-defined concepts without ability to articulate what they are, while other terms they will understand explicitly. We start by defining a few abstract terms such as digital identity, identity systems, social contexts, etc and move on to more explicitly understood terms.

As a result of exploring a typical user’s mental models of identity-related concepts, and historical patterns of human economic activities, we identify more innate concepts such as self-identities, perceived identities, accounts, conversations, messages, etc.

We then explore how multiple identities play a part of a user’s cognitive understanding of their place within multiple social contexts as well as task-based contexts with anonymous and pseudonymous identities.

Then we explore how identity-related tools and artifacts have historically been used and understood by people, including how they use artifacts that function as IDs, credentials, and/or keys, as well as how for managing large numbers of artifacts we use complementary organization and storage tools.

Building systems and applications that operate based on concepts parallel to a typical user’s mental models, will inherently result in better user experiences, as well as more intuitive understanding of underlying processes.

Definitions

As explained in “What identity means” the word “identity” is overloaded on many levels. Few regular users understand abstract words like identity, authentication, credentials, or authorization. So here, let’s reiterate the key terms and concepts that will be reused throughout this article to discuss users’ consciously or subconsciously understanding.

- Identity systems — The identity industry is built upon the building, maintaining and usage of identity systems, that ultimately help us be more efficient and secure our daily transactions against undesired outcomes.

- Identity instances — Any virtual representation of persons or organizations in any system be they digital, paper-based, or mental.

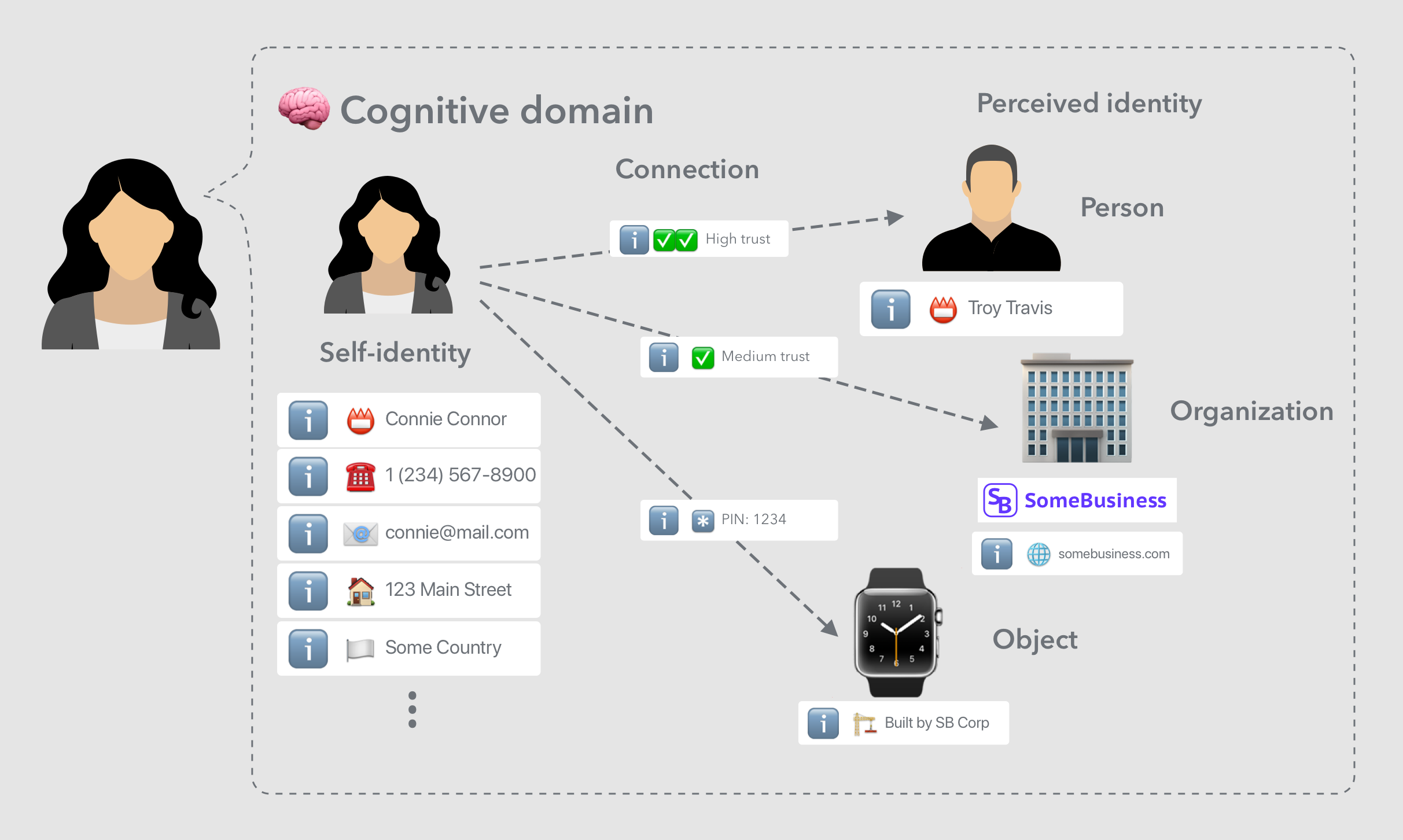

- Cognitive realm — The sometimes oversimplified approach of looking at our cognition as systems and processes, can result in valuable insights. As such the cognitive realm considers the representation and interaction of real world things as reflected onto our mental information space.

- Digital realm — As a subject of interest and source of great societal impact, digital systems are of growing importance in our lives, highlighted by the prominence of internet, web and so called “cyberspace”. The digital realm considers the representation and interaction of real world things as reflected onto digital systems in the form of data.

- Digital identities — a sub-type of identity instance — within the context of digital identity systems these are specific instances of an an entity’s representation, a digital twin so to speak. In other words, digital identities, are records of a person or organization within digital systems that are uniquely secured for common operations such as lookup, authentication, recovery, sharing, etc.

- Social context —aka Social circle — Is both a mental and sociological context that is defined within a well-known social circle. For example, close friends and professional social circles are two completely different contexts with different rules. Accordingly, we mentally identify as separate (yet related) beings depending on this context.

- Self-identity —aka Self — Is a type of mental identity instance that identifies the “self” within a given social context. For example the “self” of personal relationships is different than that of professional social circles.

- Perceived-identity —aka Identity — Is a type of mental identity instance that identifies other people or organizations, again within the context of a given social context.

- Identity information (fragment) — Additional information associated with an identity that further describes a person, organization or thing, and possibly helps identify it through language, visual or other sensory input.

Our goals in designing intuitive identity systems for consumers, will often require us to align the concepts and taxonomy used to that of our natural mental models.

Economic activities and mental models

As subjects of life evolution, we are inherently economic individuals and societies. As such our mental models have evolved with significant influence from the economic activities that most help sustain us and our societies. With this view we can look at human mental model of specific types of activities, artifacts, tools and mental contexts that are closely related to our use of identity systems.

You can argue that our minds come equipped with a cognitive identity system, one that intuitively interoperates with the real world, and is sometimes aided by external identity systems such as digital or paper-based ones, ultimately forming a hybrid system.

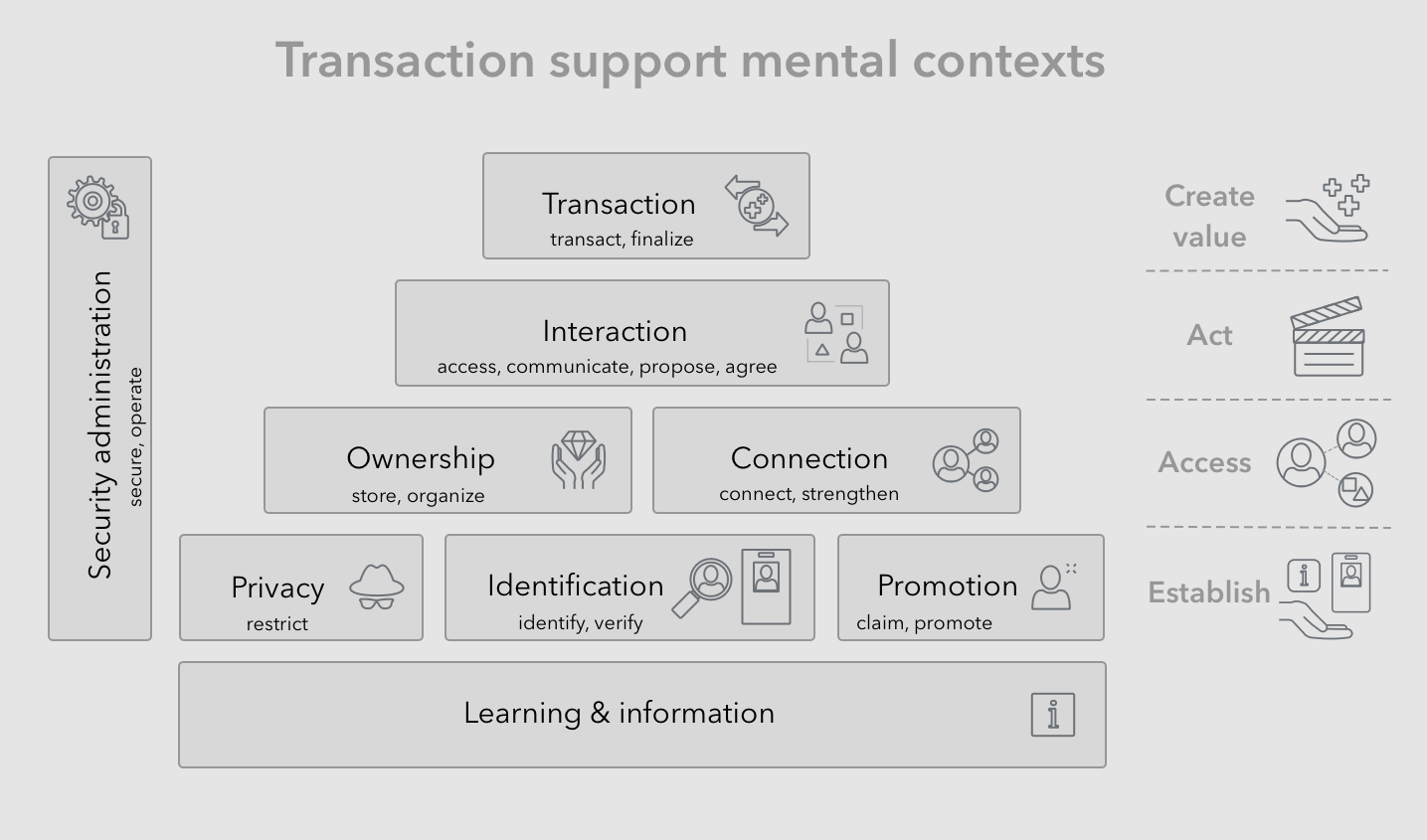

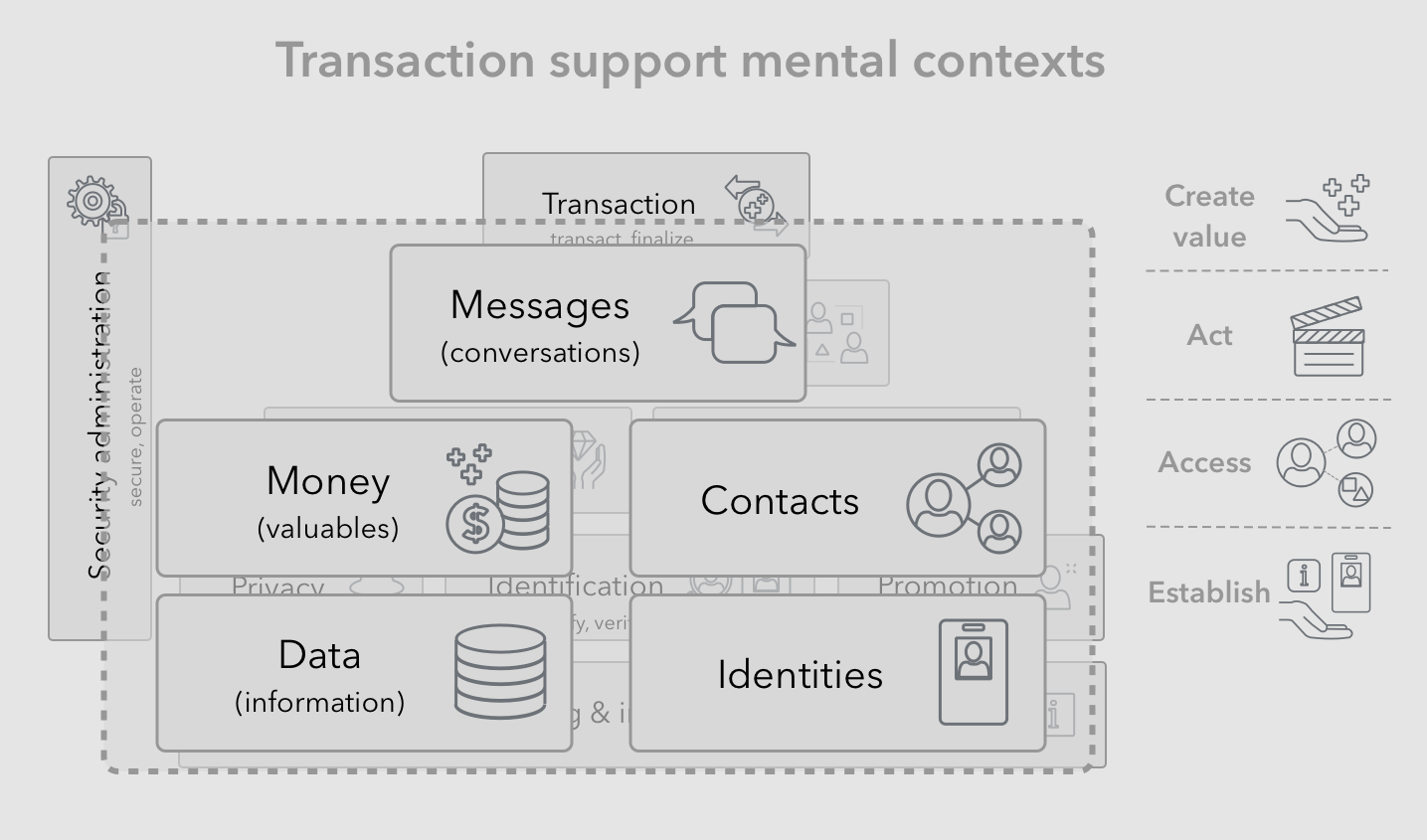

In “Economics of identity systems” we touched on the frequent and high-value activities that help us support transactions.

These activities point to five distinct mental contexts involved in said supporting activities, namely:

- Information (or data) — Is the generalized form of information about the real world, and how we organize and make sense of it.

- Identities (self and perceived) — Are the representation instances of self and others within various and specific social contexts, enhanced by trust information.

- Money (or valuables) — Is the mental monetary understanding of valuables natural to our evaluation of property, transactions and surplus.

- Connections (or contacts and relationships) — Is the mental social understanding around the state and protocols of belonging to specific groups or relationships, and the mutual expectations that go with building relationships.

- Messages (or conversations) — Is the mental orientation having to do with communication and the mechanics of conversations in terms of single or fragmented messages and their replies.

The above root level concepts are generally well understood by typical users. In addition, the following extended list of core concepts are expected to be explicitly understood by typical users, as they seem to represent innate cognitive constructs:

- Information (fragment) — Given the composability of information, humans intuitively understand and handle fragments of information for the purposes of mental storing, organizing and retrieving. A typical user however may be unable to articulate what an information fragment They can however intuitively navigate information systems such as libraries, books, newspapers, etc. Information systems such as the world wide web provide functionality of digitally publishing, addressing, organizing and consuming public information.

- Social circle (or context) — As detailed in our definitions, as humans we intuitively and explicitly aware of social circles or contexts we are a part of. These contexts vary across different groups, common goals and interests, as well as particular relationships with individuals.

- Self-identity — Depending on a given social context, we take on dynamic roles which manifests in separate but related self-identities. Simple examples are our roles and identities as parents, siblings, citizens, team members, etc.

- Self-identity information (fragment)—For each given social context and self-identity there may be unique fragments of information that we associate with ourselves and potentially present to others. For example we may take on a special nickname for designated social contexts such amongst close friends, or amongst our extended family.

- (Perceived) Identity — High level information about another person (or organization’s) is mentally stored for the purposes of identifying that person in future interactions. This is different than that person’s self-identity which belongs to them, however it is deeply affected by how that person presents themselves, and asks to be remembered. Humans may not explicitly know they are dealing with a perceived identity but they can intuitively navigate it, even with help of external tools such as directories and address books etc.

- (Perceived) Identity information (fragment) — Each given perceived identity is mentally associated with possibly unique fragments of information. For example we may remember a friend’s phone number, as well as a secret handshake between us.

- Connection (or contacts and relationships) — Perceived identities can be mentally stored even without an actual connection or relationship existing. Connections suggest the existence of some state of trust or long term understanding between two parties or an individual and a group. As such connections often require varying levels of maintenance.

- Account (or perceived connection) —When dealing with businesses who keep track of customers, we often perform the equivalent of opening up an account with them. This is essentially the other party’s record or mental store of their connection with us. The goal is often for that business and us to help maintain the state of that account in good standing.

- Conversation — As part of connections with others we may perform long-term and short term conversations with them. We may mentally store and recall the state of these conversations, or use external tools such as letters or digital messages to keep track of them.

- Message — Messages are the atomic sub-component of conversations, that can be mentally tracked individually. As humans we can intuitively recall specific messages and their contexts, as well as navigate external tools such as IM or email that enhance them.

As a result of the users’ explicit understanding of these concepts, they are expected to be intuitive to deal with as digitally represented artifacts.

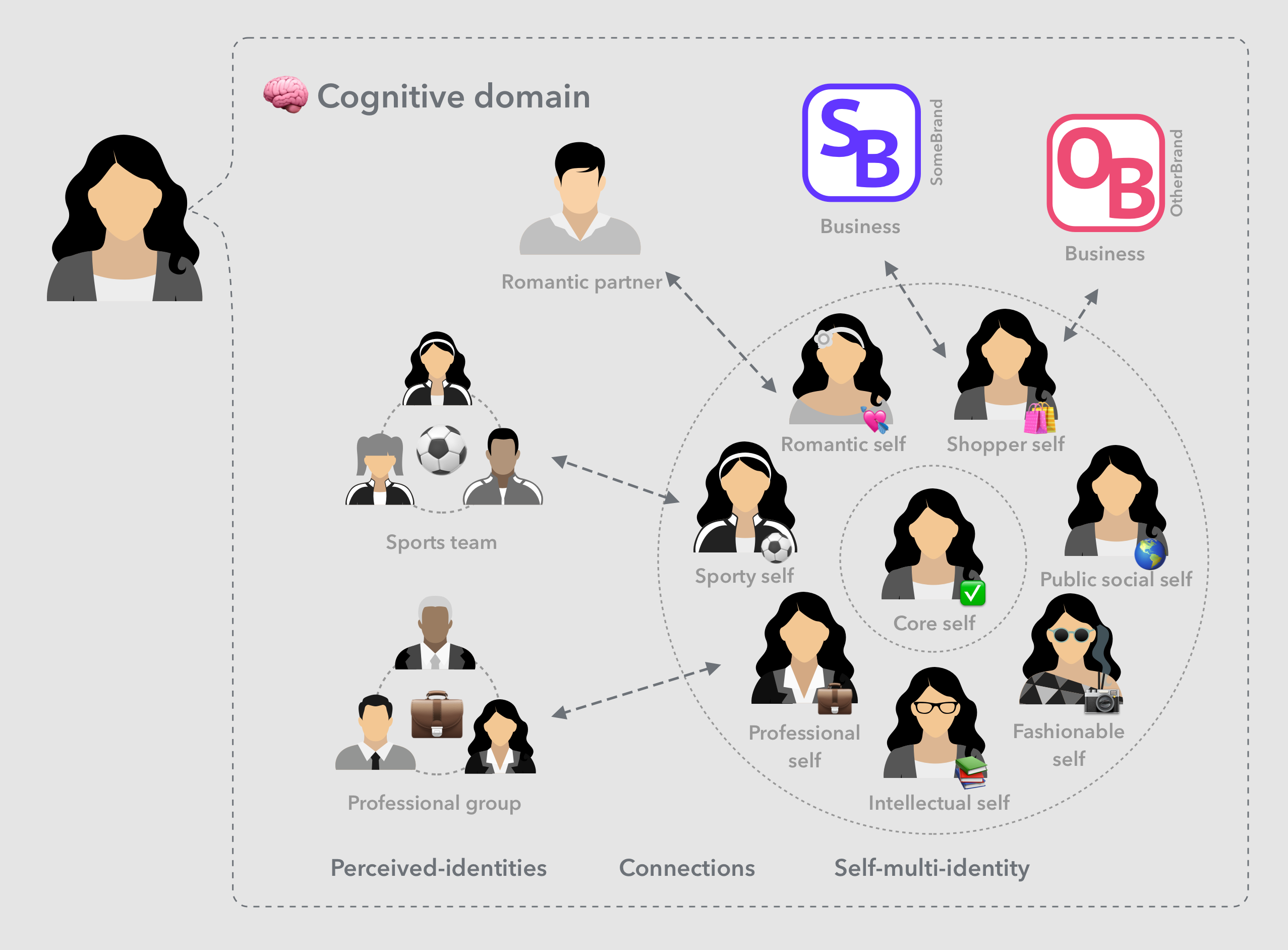

Multi-identity

As mentioned in the previous sections, a person’s self-identity is not one static thing, it morphs depending on the context of the social circle or context it is embedded in. Each of these multiple identities take on a well-defined role within their target social context, and may be associated with separate identity information fragments.

A list of some well known social contexts include but are not limited to:

- Core — this is what a person means to themselves. It represent ones relationship to themselves and the core of one’s identity.

- Public (social) — This is the most public aspect of our self identities there for all to see. This context has not commonly existed before the advent of internet and social networks. An example of the digital representation of our identity in this context is our facebook public profile.

- Social (within a given circle) — A context meant mainly for general socializing and forming medium strength social connections within a social group bound by factors such as class, geography, beliefs, or other factors.

- Professional (in a given field) — The context represented by professionals working within a given group with the same company, organization, career path, specialization, etc. LinkedIn is a typical professional social network.

- Intellectual (general and/or in a given intellectual field)— A social arena where people pursue thought leadership or patronage in order to share or add to their intellectual prowess. Specific fields of academia fit this context. Also twitter can be typically identified as an intellectual-based social network.

- Sports (general and/or a specific sport)— A social community where people may share and consume sports news, reactions and trivia as well as participate in actual sport competitions. The team a person plays sports on, or the office’s sport tournament bracket are examples of such contexts.

- Romance (and/or sexuality)— Social networks or mutual relationships based on romance or possibility of finding it. Dating networks or events, as well as people’s romantic relationships are examples of such contexts.

- Family (core and/or extended)— Social groups based on family relations be they small and intimate or larger and more extended. A person’s immediate family including partner and children, or extended family such as grandparents and cousins are examples of such contexts.

- Friends (core and/or extended) — A group of mutual friends, a pair of best friends, or the larger circle of past friends can make up the friends social context. Acquaintances — The larger circle of temporary or relatively weak social relationship that we maintain in case they become advantageous at a later time. Networking activities and events are one of the way people gain new acquaintances.

- Retail (or other consumption)— The relationships we have with brands and companies we transact with to purchase goods, products and services. These relationship contexts are often isolated and transactional, although they may be persistent across sessions of interaction.

- Citizenship (local, state and/or national)— The social context of belonging and feeling allegiance to a given locality, state or nation. This often comes with a sense of community and loyalty to the larger entity.

- Common interest (or hobby)— A social group brought together by common interests such as a hobby, technology, activity or topic. Such social contexts often benefit from a sense of community due to the fringe nature of the participants’ interests.

There are certain task-based relationships where one’s self identity is not consequential. Often such tasks can be completed using a completely or partially anonymous identity, at other times they can be accomplished using a synonymous identity that is correlated across sessions yet unidentified and uncorrelated to other identities.

- Anonymous — A completely unidentified and un-correlate-able one-time-use identity. This type of identity offers maximum privacy benefits.

- Incognito — aka partially anonymous - Mostly anonymous with some correlate-able or identifiable information out of necessity. It is essentially a partially anonymous identity for when complete anonymity cannot be achieved due to technical or environmental limitations.

- Pseudonymous — An unidentified persona that is correlate-able across sessions. It is used when anonymity is desired but some state across sessions is required for things to go smoothly.

For example buying a pack of cigarettes from a convenience store using cash can be done mostly anonymously, however creating content and building reputation in social media can be done pseudonymously. Browsing the internet can be performed in incognito mode which is mostly anonymous but leaks information such as your IP address.

Identity as a tool

Often the way identity concept manifest themselves in the external physical or virtual worlds has to do with how we use “identity” as a tool for accomplishing everyday tasks.

In “The economics of identity systems” we take an in depth look at how we historically use identity-related artifacts and tools, and reveal the insight that despite going various waves of technologies, we have been using them to accomplish the same set of activity verbs.

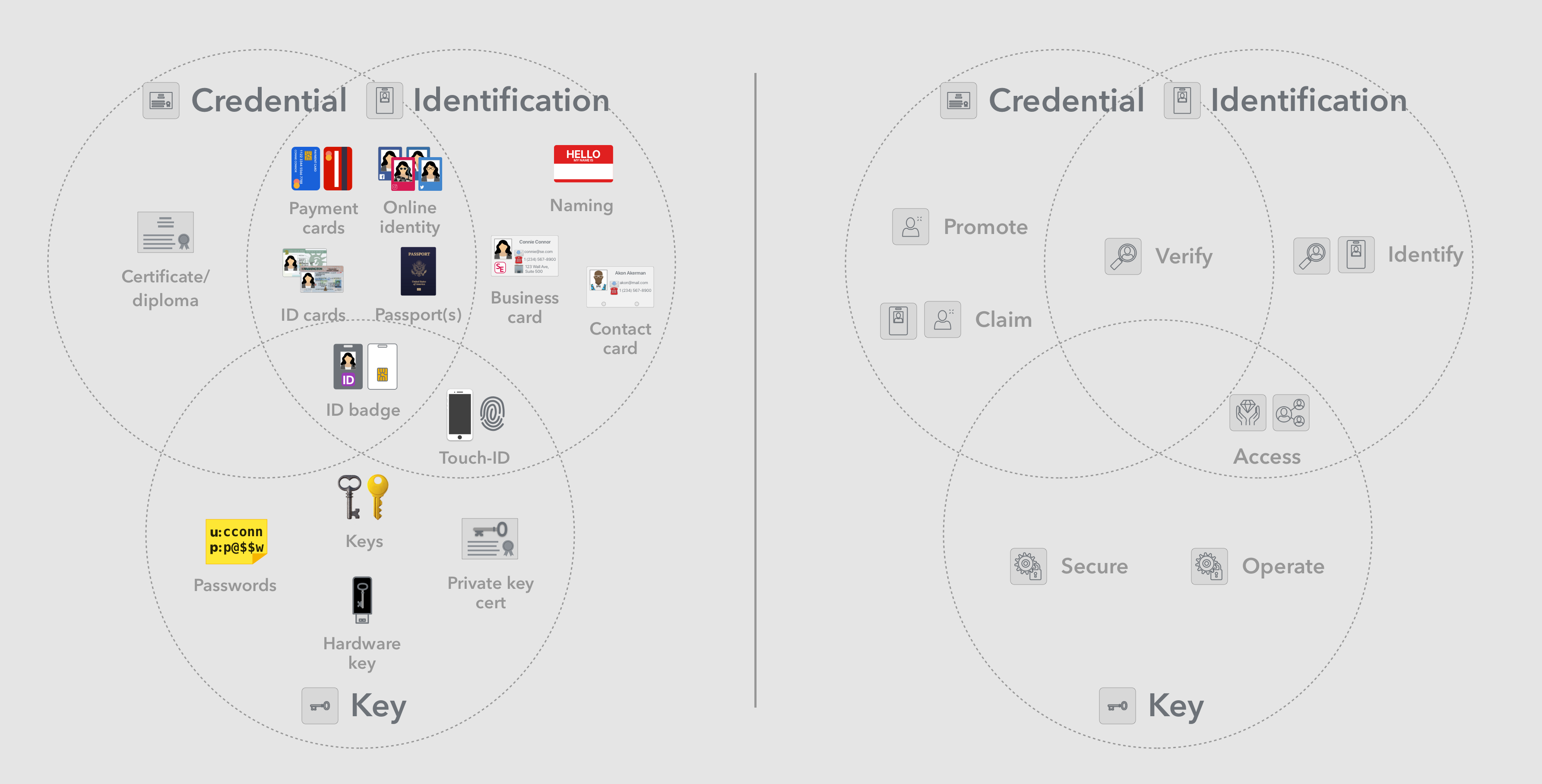

Artifacts we tend to use by the name ID, identification card, or identity, across different technology waves have historically performed a combination of one, some or all of the following functions:

- Identification artifact — aka ID (or identification document) — Act as a medium for the user to communicate identifying information such as name, address, etc to another party in order to facilitate a mutually beneficial transaction.

- Credential — Is used to present a claim and/or to promote the user’s perceived level of trustworthiness to a transaction participant, by demonstrating verification by a trusted third party.

- Key — Is used to securely interact with a system and access its functions, as the system prevents unauthorized parties from access. This is typically done by authenticating the key artifact used and trusting that the holder was originally granted that key, or is authorized by the grantee.

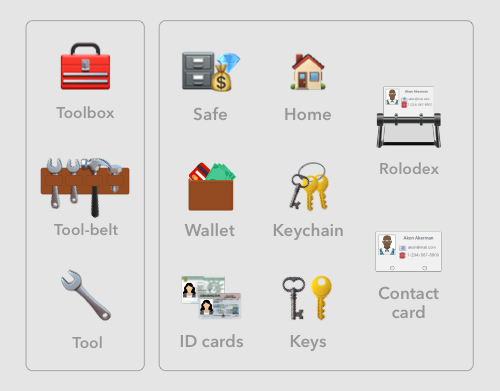

When dealing with a large number of these artifacts and tools, we often resort to using additional organization and access of tools. These tools in turn seem to naturally function in parallel to how we mentally organize and access the related concepts.

For example for physical tools like hammers and wrenches, we use complementary tools such as tool-belts and toolboxes to either temporarily store and immediately access them, or store them for longer term storage and access.

For artifacts such as ID (identification document) cards, keys, payment cards, or contact cards we utilize similar storage and organization tools such as wallets, keychains, and rolodexes.

Conclusion

Our ultimate goal of understanding the mental models of typical users is building intuitive identity systems and applications. They need to operate based on parallel concepts to said mental models in order to achieve better user experiences and intuitive processes.

This article takes a good stab at identifying concepts that are likely to be innate to human cognitive constructs, and how multiple identities innately make up people’s understanding of themselves. It also touches on the common patterns of artifact and tool usage, as well as complementary storage and organization tools.